Furniture design and manufacturing, and ship model building, may appear distinct undertakings. However, upon closer examination, they share commonalities. Both endeavors demand substantial intellectual capabilities, including design and research, as well as manual skills for actual construction. The primary difference lies in the scale of the work.

Furniture design encompasses a harmonious blend of diverse attributes, such as beauty, comfort, and practicality. It is an exercise in juxtaposing three fundamental values: aesthetics (appearance), engineering (physical attributes), and woodworking (execution). This combination makes furniture design and manufacturing an engaging, rewarding, and challenging pursuit.

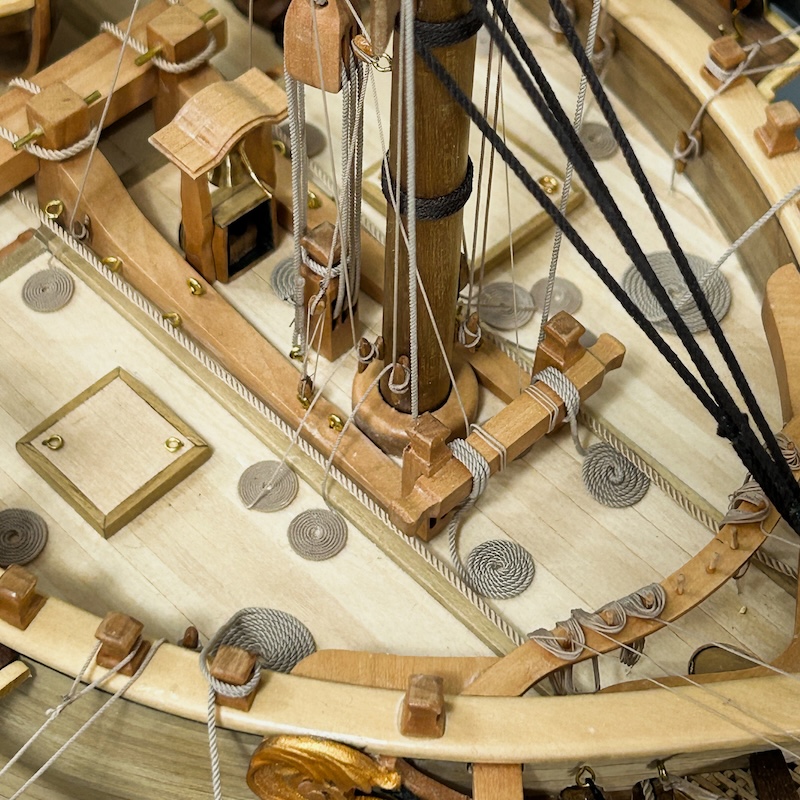

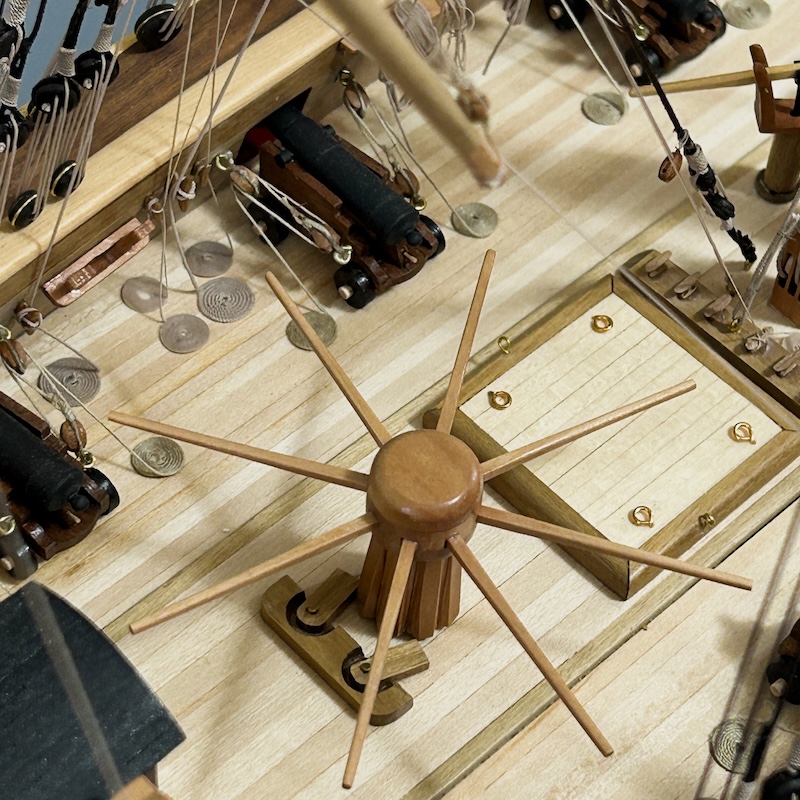

My ship model building process invariably commences with research. Whenever feasible, my models are constructed using existing historical documentation, capturing the essence of real ships and conveying the stories of their designers, builders, captains, and courageous crews who navigated them.

My engineering background provides a technical foundation for my furniture designs, while the woodworking skills stem from my early years spent crafting ship models, ranging from small to large, even models of ships in bottles. Subsequently, I gained experience in building actual sailing boats.

My visual acuity and deep appreciation for craftsmanship were profoundly influenced by the art movements of the early 20th century, particularly the Wiener Secession (Vienna Secession), Wiener Werkstatte (Vienna Workshops), Art Nouveau, and, arguably most significantly, Bauhaus.

Over time, aesthetic preferences undergo evolution, influenced by new experiences and acquired skills. Furniture design and making, as well as ship model building, remain perpetual quests for enhancing beauty, comfort, and functionality.

Furniture can be appreciated for its aesthetic qualities, simplicity, sophistication, or any other attributes that evoke positive emotions and persuasion. Ship models, on the other hand, serve as remarkable historical witnesses, preserving the legacy of past, age of sailing, maritime endeavors.

dressers and cabinets

desks and tables

chairs

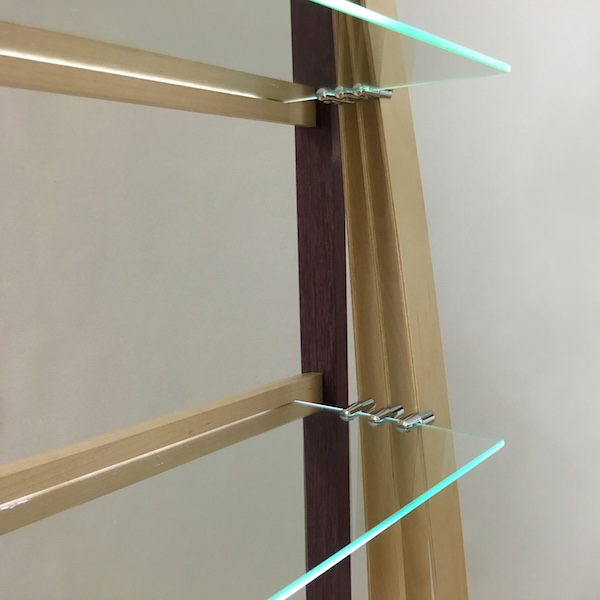

shelving

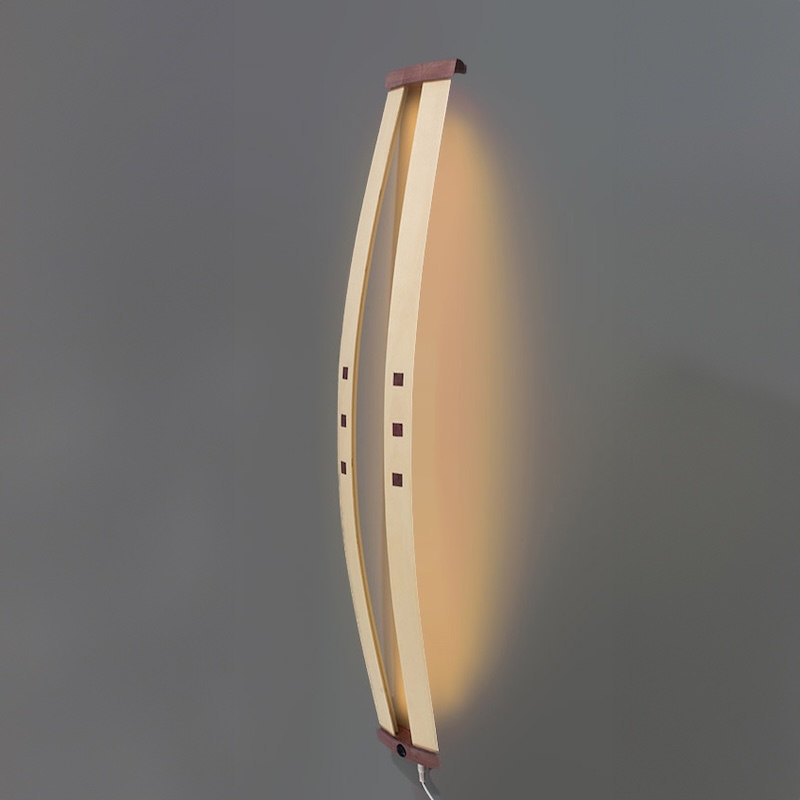

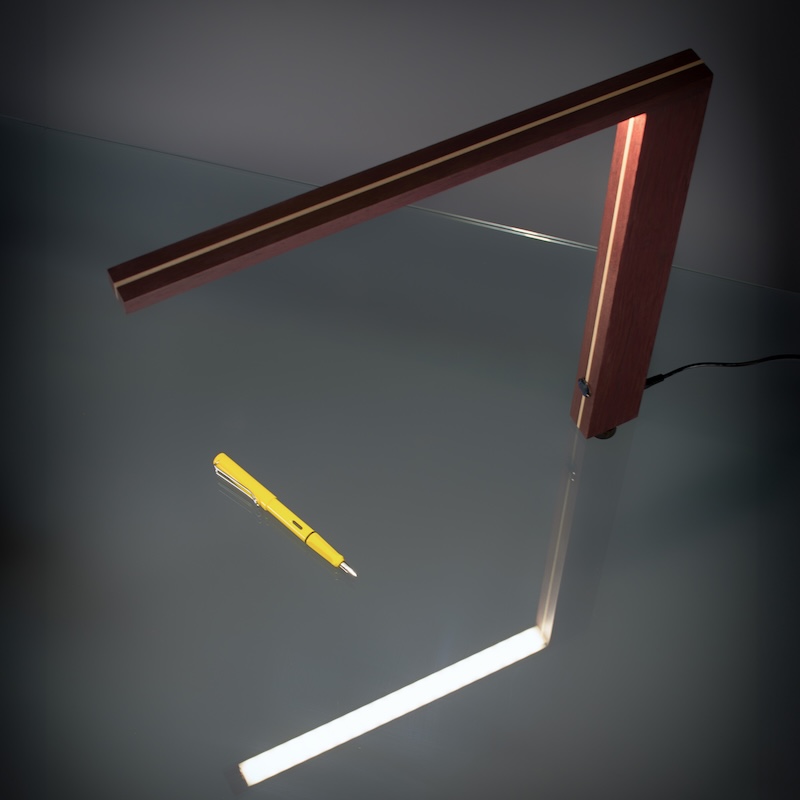

lamps

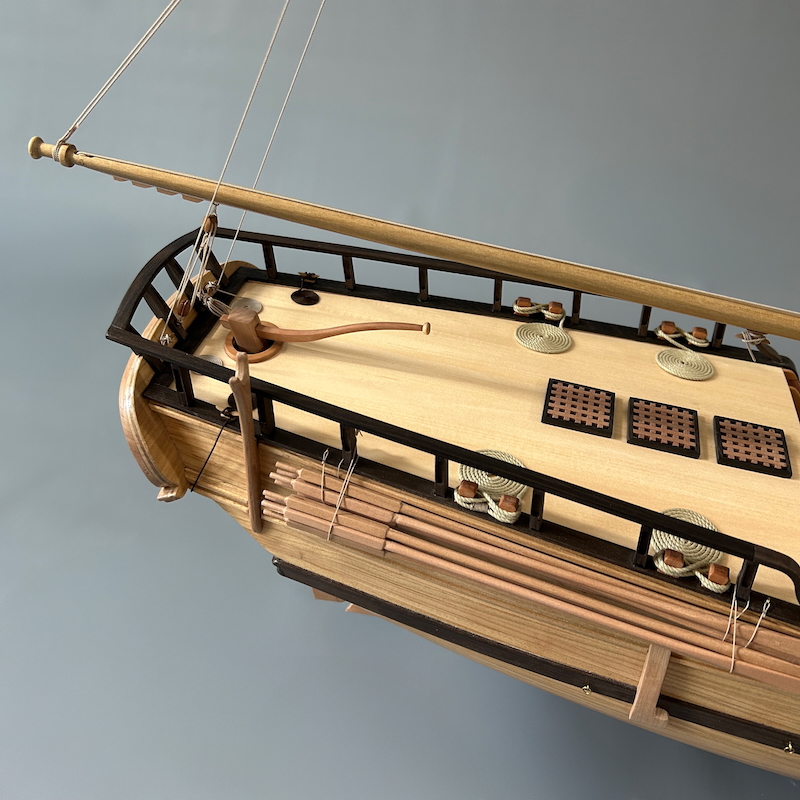

le Rochefort - port yacht

built: 1787 (no later known history)

Rochefort, France

design: Hubert Penevert (1754-1827)

original specifications:

length: 54 ft

beam: 15 ft

tonnage: 60 ton (approx.)

crew: 8 men (including master)

model scale 1:24 (POF)

historical notes

Although Port Yacht Le Rochefort was a diminutive utilitarian vessel constructed during the reign of Louis XVI, its origins were intrinsically linked to French naval history during the reign of Louis XIV.

In approximately 1660, the French court recognized the inadequacy of Brest, the sole substantial French naval base on the Atlantic coast at the time, to support Louis XIV’s ambitious maritime strategy. A compelling need for a second shipyard between Brest in Bretagne and Spain became evident. Consequently, the region encompassing the delta of the Charente River was designated as the prospective location for the shipyard.

However, unresolved disputes between the French court and the actual landowners in the vicinity, particularly near the coast, led to the selection of Rochefort. Despite being situated significantly upstream of the Charente River, as compared to other initially considered locations, reasonable navigability of the river was a decisive factor in viability of Rochefort selection. Nevertheless, it remained approximately 18 kilometers from the sea.

To address the challenges posed by the Charente River’s depth and width, it was understood that vessels constructed in the shipyard or returned for service and maintenance would need to travel up and down the river devoid of armament, and with only the essential equipment. This necessitated the development of a specialized fleet of small vessels known as port yachts and chattes (aka lighters — flat-bottomed barges), designed to transport equipment, armament, provisions, gunpowder, and other supplies to the ships once they were back in the deeper waters of Aix harbor, near the Charente River estuary. While port yachts and chattes were both service boats, port yachts had some unique construction features to allow for safe transportation of - in particular - gun powder and munitions.

Rochefort became a bustling shipyard, and historical records indicate the construction of at least 23 port yachts between 1674 and 1787, suggesting a substantial volume of shipbuilding activities in the area. Notably, the design origins of port yachts can be traced back to the Netherlands. Early in the 17th century, Dutch engineers were brought in to drain the Aunis marshes (just north of Rochefort), bringing with them expertise in construction of vessels specifically tailored for canal navigation. Consequently, certain distinctive features of the Le Rochefort's hull frame and rigging bear a clear Dutch influence.

Le Rochefort, constructed in 1787, was designed by Hubert Penevert. It served as a replacement for another port yacht named Le Rochefort, which was designed by Geslin le cadet in 1750 and demolished in 1786. Both vessels fulfilled the same purpose and shared numerous similarities. The plans of both vessels were preserved in the Rochefort archives and were then used to recreate the original design of Penevert’s ship. Fortunately, more detailed notes, particularly those describing the framing and masts, of the second Le Rochefort also survived.

The "Le Rochefort" monography by Gerard Delacroix (published by Ancre) provides very interesting insights into origins and history of port yachts in general, and Le Rochefort in particular.

la Volage - barque longue

built: 1693 (last existing record 1706)

Dunkirk, France

design and construction:

René Le Vasseur (1667-1727)

original specifications:

length: 63.5 ft

beam: 16 ft

tonnage: 60 ton (approx.)

crew: 50 men (2 officers)

armament: 10 4-pounder guns

model scale 1:24 (POB)

historical notes

La Volage, constructed in 1693 by René Le Vasseur (1667–1727) in Dunkirk, France, was one of 26 barques longues built by Le Vasseur between 1690 and 1726. Notably, the last six were constructed in Toulon, where Le Vasseur relocated from Dunkirk. Historical records reveal that from 1666 to 1708, over 80 ships classified as barques longues were constructed in various French shipyards

The strategic significance of Dunkirk’s port led to the proliferation of the barque longue class of ships. In 1662, Dunkirk became French property, acquired from Charles II of England. It is plausible that the British regretted the sale, as it enabled France to monitor and control ship traffic in the English Channel during the perpetual privateering wars against English commerce. The barque longue was an ideal vessel for this mission.

What was “barque longue”?

Defined as a long boat or longa barqua in the French Royal Navy, the barque longue was classified as the lowest rate ship (below light frigate). Dunkirk’s barques longues were predominantly constructed for privateering purposes, contributing to the city’s reputation as a privateering hub. Despite their privateering origins, they remained part of the French Royal Navy under Louis XIV. The unique geographical environment of the Dunkirk coast had a profound influence on ship design. Surrounded by shallow waters, the ships built and operated from Dunkirk were designed to minimize water displacement. Given the limited armament (small caliber cannons), they prioritized speed, maneuverability, and exceptional sailing characteristics.

The design of the barque longue appears to share some common characteristics with earlier, smaller boats known as simple barks, which were commonly used along the coast of Brittany. However, given that Dunkirk was under Spanish control during the 16th and 17th centuries, the design of Spanish caravels could have also influenced the design and construction of ships in Dunkirk. Certainly, there are notable similarities between all of them, particularly in rigging.

The barques longues gradually evolved into the corvette class towards the end of the reign of Louis XIV.

While numerous references to barque longue can be found in various archives, there has been limited research into the more detailed history of this type of ship. The most recent monography by Jean-Claude Lemineur has addressed this gap and provides a comprehensive account of the barque longue. His book and plans were subsequently utilized to construct a model of the ship.

l'Amarante - corvette

built: 1747 (wrecked: 1760)

Brest, France

design and construction:

Joseph-Louis Ollivier (1729-1777)

original specifications:

length: 89.5 ft

beam: 23.5 ft

tonnage: 220 ton

crew: 94 men (4 officers)

armament: 12 4-pounder guns

model scale 1:36 (POB)

historical notes

The L’Amarante, constructed in 1747, was the final of three corvettes of the La Palme (1744) class, with the other being L'Anémone. All three ships were designed by Blaise-Joseph Ollivier (1701-1746), but the completion and construction were carried out by his son Joseph-Louis Ollivier (1729-1777) in Brest - at the age of 15. Joseph-Louis Ollivier had already begun working with his father at the age of 9, which explains his expertise and knowledge necessary to build ships of that size.

The class of corvette (sometimes also referred to as sloop of war) had become an essential component of any navy during that era. Smaller than frigates, they possessed light armament, which rendered them less effective in combat. However, their primary distinction lay in their exceptional speed and maneuverability. These characteristics made them ideal for delivering orders, monitoring enemy vessels, providing convoy assistance, and safeguarding against privateers.

Blaise-Joseph Ollivier was France’s most prominent and influential naval architect of his time. Among his numerous published documents and dissertations, a 1736 treatise provided a detailed description of the construction and features of corvettes (sloops of war). Later, he also identified two types of corvettes: 12-gun and 16-gun versions. The design and characteristics of the La Palme class closely reflect Ollivier’s ideas for the 12-gun corvette. As relatively smaller ships in the French Navy, corvettes did not feature elaborate decor, which was a characteristic of larger ships of the line. This principle also applied to L’Amarante and her sister ships.

L’Amarante served in the French Navy in various missions and engagements. Her first commander was M. de Foucault, and one of her early accomplishments was the capture of the British privateer Prince of Wales in 1748. She was later commanded by Gabriel de Bory (1751), whose mission was to conduct astronomical observations in Vigo and along the coasts of Spain and Portugal. While there were other commanders, documentation is quite limited. She primarily operated along the Atlantic coast of France, from Dunkerque in the north to the coasts of Spain and Portugal in the south. Eventually, in February 1760, she was wrecked near Saint-Malo while on a mission to land in Ireland (the entire operation, including five frigates and 1200 troops, was led by privateer François Thurot).

The L’Amarante model is based on a multitude of historical sources. The majority of available historical documents are contained in the excellent monography “L’Amarante” by Gerard Delacroix, published by Ancre. This monography is a collection of captivating historical records that reflect the evolution of naval architecture and the general theory of corvette design and construction. The monography also includes detailed drawings that were utilized in the construction of the model.

la Siréne - frigate

built: 1744 (captured: 1760)

Brest, France

design and construction:

Jacques-Luc Coulomb (1713-1791)

original specifications:

length: 127 ft

beam: 33 ft

tonnage: 615 ton

crew: 206 men (10 officers)

armament: 26 8-pounder and 4 4-pounder guns

model scale 1:4 (POB)

historical notes

La Siréne was the inaugural vessel of the La Siréne frigate class, a fifth-rate frigate, alongside La Renommée. Both ships were designed by Jacques-Luc Coulomb (1713-1791), who also constructed La Siréne. La Renommée was built by François-Guillaume Clairain des Lauriers.

The design was inspired by Blaise-Joseph Ollivier’s seminal theoretical naval architecture dissertation, “Traité de Construction”, published in 1746. This work established the fundamental principles of hull design, emphasizing seaworthiness, speed, and other essential characteristics. For many years, it became the de facto standard for ship design.

Blaise-Joseph Ollivier was also engaged in a covert industrial espionage mission to England and the Netherlands, conducting extensive surveys of shipyards in both countries. His observations were recorded in “Remarques sur la Marine des Anglais et des Hollandais faites sur les lieux en 1737”, which resulted in substantial improvements in the French shipbuilding industry.

In contrast, both La Siréne and La Renommée had distinct histories.

La Siréne participated in numerous French naval campaigns until 1760, when she was captured by the British Navy off the coast of Cuba. However, she was never incorporated into the British Navy.

La Renommée served under French colors only until 1747, when she was captured by HMS Dover. Recognizing the exceptional nautical qualities of the ship, the British Navy commissioned her under the name Renowned and she continued to serve until 1771, when she was decommissioned and broken up.

The model of La Siréne is based on a combination of historical sources. While the original details of La Siréne are not well-preserved, her sister ship La Renommée is extensively documented in Jean Boudriot’s comprehensive monography “La Renommée.” Additionally, the hull lines of La Siréne were included in Fredrik Henrik Chapman’s “Architectura Navalis Mercatoria”.

Bluenose - schooner

built: 1921 (wrecked 1946)

Lunenburg NS Canada

design: William James Roué (1879-1970)

construction: Smith and Rhuland

original specifications:

length: 111 ft

beam: 27 ft

tonnage: 370 ton

crew: 20 men

model scale 1:48 (POB)

historical notes

The Bluenose was a famous racing and fishing schooner that belonged to the Gloucester schooner class, primarily known for its fishing operations in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. While the shallow waters of the Grand Banks were renowned for their abundant fish population, including cod, swordfish, haddock, and capelin, they were also characterized by exceptionally challenging conditions, including rogue waves, fog, icebergs, sea ice, hurricanes, and nor’easter winter storms. This environment fostered the development of the Gloucester schooner, a highly capable and seaworthy fishing vessel.

Designed by William J. Roue, Bluenose was initially intended for fishing purposes, specifically targeting cod. However, Roue, a self-taught designer, also incorporated racing capabilities into the vessel’s design, having previously crafted recreational and racing yachts.

Bluenose achieved remarkable feats, setting a record for the largest catch of fish brought into Lunenburg. It also earned the moniker of the “Queen of the North Atlantic”, having won multiple Fishermen’s Trophies in the 1920s and 1930s under the command of Angus Walters. Notably, Bluenose’s speed was legendary, with a sail area of 10,000 square feet, it attained an average speed of 14.5 knots in certain races.

As a historical footnote, the origins of the International Fishermen’s Race can be traced back to July 1920, when Nova Scotia fishermen were astounded to discover that the organizers of the America’s Cup had postponed races due to wind conditions deemed too strong (23 knots). For those who fished the shallow waters off Canada’s east coast, this wind was merely a stiff breeze. Consequently, an annual tradition of the International Fishermen’s Race was established, honoring the working fishing schooners of the region.

As the salt fishery declined, Bluenose was sold in 1942 to the West Indies Trading Company. In 1946, while sailing near Haiti, Bluenose hit a reef and sank.

The Bluenose, a renowned schooner, achieved “immortality” when its image was inscribed on the Canadian dime. It is widely regarded as the most celebrated vessel in Canadian maritime history.

The Bluenose model was constructed using original blueprints of the Bluenose, which are housed in the collection of the Halifax NS Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. During the ship’s construction, there were some modifications that were accepted and approved by William J. Roue, all of which are well documented. The Bluenose replica, Bluenose II (which still exists), also provides valuable insights into the design of the original vessel.

Coeur de Lion - clipper

built: 1854 (sank 1915)

Portsmouth NH USA

design and construction:

George Raynes (1799-1855)

original specifications:

length: 176 ft

beam: 36 ft

tonnage: 1300 ton

crew: 20 men (approx.)

model scale 1:72 (POB)

historical notes

Coeur de Lion epitomizes the most romantic era of the Age of Sail, driven initially by the demand for tea from China and subsequently by the need for wool from Australia. This necessitated the conception of a new class of ships, the clippers, which emerged in the mid-19th century. These merchant sailing vessels possessed an unparalleled combination of speed and cargo carrying capabilities.

Clippers, renowned for their elegant hull lines and substantial sail area, harnessed the power of Trade Winds to achieve remarkable speeds. However, their operation demanded exceptional sailing skills. The advent of the steam engine and the opening of the Suez Canal brought an end to the clippers’ era.

Coeur de Lion, a medium-sized clipper, was designed and constructed at the renowned shipyard of George Raynes in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Raynes and his shipyard had a proven track record in designing and constructing clippers. Coeur de Lion was commissioned by William F. Parrott, Esq., and initially captained by George W. Tucker, a highly esteemed sailor.

The vessel embarked on a global voyage, with its first recorded journey from Boston to San Francisco spanning an impressive 133 days. Over the years, Coeur de Lion changed ownership several times before ultimately meeting its demise in September 1915 when it sank in the Baltic Sea after colliding with another ship, the SS Rossmer.

A remarkable painting depicting Coeur de Lion is preserved in the Smithsonian Institution’s collection in Washington, D.C. For enthusiasts of ship modeling, blueprints of Coeur de Lion have survived, providing invaluable insights into the ship’s hull design and deck equipment. Numerous books dedicated to American clippers frequently mention Coeur de Lion, offering further details and historical context. Additionally, historical records pertaining to the vessel are preserved at the Portsmouth Athenaeum in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Galleon

built: 1570-1572 (never launched)

Elbing (Elbląg), Poland

design and construction: Venetians (Stefano Cristiano, Dominico, Iacopo)

original specifications:

length: 90 ft (approx.)

beam: 30 ft (approx.)

tonnage: 350 ton (approx.)

crew: 60 men (approx.)

armament: 12 guns (approx.)

model scale 1:48 (POB)

historical notes

The construction of the Galleon commenced in Poland in 1570 by the Maritime Commission, the first Polish admiralty established in 1568. The commission’s mandate was to fulfill King Sigismund II August’s vision of establishing a regular Polish Navy. As part of this project, three ships were ordered, with the largest vessel designated as the Galleon.

The construction of the Galleon commenced in 1570 and lasted through 1572. However, the passing of King Sigismund II August in 1572 brought an end to the Maritime Commission’s activities, leaving the ship unfinished.

The sole reliable and captivating documentation of the Galleon’s construction is Adam Kleczkowski’s “Register of Galleon Construction”, published in 1915. This document is primarily based on original records detailing the expenses incurred during the ship’s construction. Jan Bakowski, who served as the Maritime Commission’s administrator at the time, provided a comprehensive account of the financial aspects of the undertaking.

Unfortunately, no preserved plans of the Galleon exist, and there are no specific characteristics, such as its name, size, number of guns, or rigging. Numerous attempts have been made to define these aspects based on speculation rather than concrete evidence. The absence of surviving documentation further complicates the matter.

One intriguing aspect of the Galleon’s history is the research into its designers and builders. It appears that King Sigismund II August, whose mother was Italian (Bona Sforza), sought assistance from Venice, a prominent maritime power at the time with exceptional shipbuilding expertise. According to records, the design of the ship was finalized in Malborg (Malbork), while its construction took place in Elbing (Elbląg).

The model of the Galleon, due to the lack of detailed documentation, serves as a representation of a period ship and does not necessarily reflect the actual vessel constructed in 1570. Nevertheless, if actual ship had ever been completed, it would have been a fascinating ship.